Caring for ligament sprains demystified!

Author: Meredith Butulis, DPT, ACSM HFS

Welcome to Part Two of our three part series on muscle, ligament, and bone injuries. We will explore some common myths and how you can use current evidence to efficiently return to optimal performance. This month we will explore ligamentous injuries.

“It’s just an ankle sprain; can I perform this weekend?”

“My hip flexors are always tight, so my friend taught me the frog stretch; is this a good stretch?”

As dancers, teachers, or allied health professionals, we’ve likely experienced questions like these.

What are some essential pearls that dancers, teachers, and allied health providers need to know when it comes to preventing and caring for ligamentous injuries?

What is a ligament and what does it do?

A ligament is a connective tissue in the body that connects a bone to another bone. Ligaments serve to create stability in the joint structure. Injury to a ligament is called a sprain, which is different than a muscle or tendon injury.

Myth # 1: After resting a new sprain for a few days, the dancer will be ready to return to the stage.

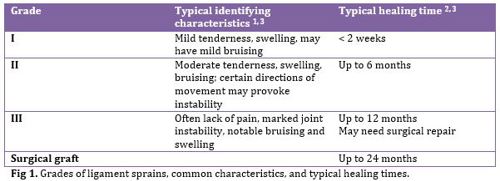

Fact: Ligament healing depends on the grade of the sprain, location, and overall health of the dancer.

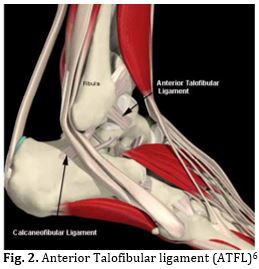

However, the most common sprain, that involving the ATFL (anterior talofibular ligament) in the ankle, notably takes 6 weeks to 3 months to achieve mechanical stability4, with 30% of these sprains continuing into a state of chronic instability.5

Dancers may wonder if they should see a medical provider if they suspect a sprain. A correct diagnosis will help lead to the most efficient route of correct treatment. There are a few indicators that should lead a dancer to see a medical provider initially, as opposed to trying self-treatment for a few days. These indicators are known as the Ottawa and/or clinical prediction rules, and further medical evaluation should be performed. Since these findings indicate possible fracture, we will discuss them in next month’s blog post on bony injury.

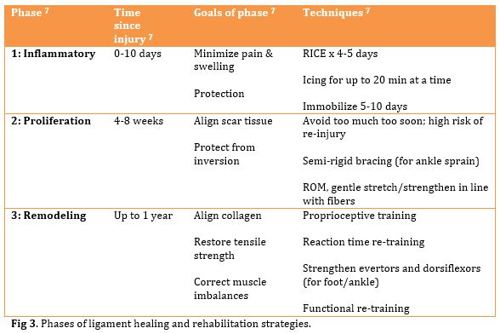

Myth #2: New ligament injuries should be treated with PRICE (protect, rest, ice, compress, elevate) for 2-3 days followed by gradual return to activity.

Fact: Rehabilitation strategies depend on the type of injury and its phase of healing. Current evidence supports matching rehabilitation strategies to healing phases. 7

Within this decade, sports medicine has also revealed that ligament sprains are more than a localized injury; they affect the entire kinetic chain and sensorimotor system of the body. 7, 8 Therefore, rehabilitation needs to include these elements. Details on proprioceptive training can be found in the International Association of Dance Medicine & Science’s resource paper, Proprioception.9 Details on progressions of functional training can be found in General Considerations for Guiding Dance Injury Rehabilitation in The Journal of Dance Medicine and Science. 10

Myth #3: Stretching is the best strategy to prevent sprains.

Fact: Stretching can be part of an injury prevention program, as it can help to improve joint alignment and neuromuscular efficiency; however, stretching by itself has not been proven to prevent injury. 11 Currently, there is not a consensus on best prevention, as injury prevention involves addressing the individual within the context of his/her abilities, movement tasks, and environment. 7, 8, 10

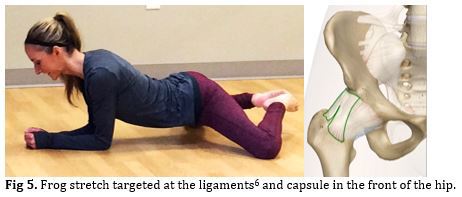

Generally, stretches should be reserved for muscles, not ligaments. One should not attempt to stretch his or her ligaments, as they may excessively elongate and fail to stabilize the joints that they protect. 12

Here is an example of a popular dance “frog” stretch targeted at the ligaments and capsule in the front of the hip. Since the stretch targets ligaments and the joint capsule, it is not recommended.

Instead, alternatives like stretching the hip adductors or hip flexors would provide safer and more muscularly targeted stretches.

Clinically, I have found that when dancers are instructed in how to stretch muscles instead of ligaments and joint capsules, their pain often decreases; their functional pain free range of motion often improves within a couple of weeks.

Concluding thoughts:

Now that we’ve explored ligament sprains, myths, and samples of current recommendations in prevention & treatment, how will you utilize this information in your practice?

Meredith Butulis, DPT, MSPT, CIMT, ACSM HFS, NASM CPT, CES, PES, BB Pilates is a dance-specialized Physical Therapist, Personal Trainer, Pilates Instructor, and dance performer. With over 15 years of experience, she is based in Minneapolis, MN at Twin Cities Orthopedics and the Minnesota Dance Medicine Foundation.

References

1. Manske RC. Postsurgical Orthopedic Sports Rehabilitation: Knee & Shoulder. Philadelphia, PA: Mosby. 2006.

2. Axe MJ, Snyder-Mackler L. In: Current Concepts of Orthopedic Physical Therapy, Independent study course 21.2.11, 3rd Ed. Manal TJ, Hoffman SA, Sturgill L. American Physical Therapy Association. 2005.

3. Haddad SL. Sprained ankle. OrthoInfo. American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons. 2016. Available here.

4. Hubbard TJ, Hicks-Little CA. Ankle ligament healing after an acute ankle sprain: an evidence-based approach. J Athl Train. 2008; 43(5): 523-529.

5. Wilkstrom EA, Hubbard-Turner T, McKeon PO. Understanding and treating lateral ankle sprains and their consequences: a constraints-based approach. Sports Med. 2013; 43(6): 385-93.

6. Phuc L. Human Anatomy System: Skeletal System (Free App for iPhone)

7. Petersen W, Rembitzki IV, Koppenburg AG, et al. Treatment of acute ankle ligament injuries: a systematic review. Archives of Orthopaedic and Trauma Surgery. 2013;133(8):1129-1141.

8. Fulton J, Wright K, Kelly M, et al. Injury risk is altered by previous injury: a systematic review of the literature and presentation of causative neuromuscular factors. International Journal of Sports Physical Therapy. 2014;9(5):583-595.

9. Batson G. Proprioception. International Association of Dance Medicine and Science. Resource paper. 2008. Available here.

10. Liederbach MJ. General considerations for guiding dance injury rehabilitation. JDMS. 2000; 4(2): 54-64.

11. Clark MA, Lucett SC, Sutton BG, Eds. NASM Essentials of Personal Fitness Training, 4th Ed. Baltimore, MD: Wolters Kluwer; 2012

12. Norkin CC, Levangie PK. Joint Structure & Function, 2nd Ed. Philadelphia, PA: FA Davis; 1992.

Further Reading

1. Critchfield B. Stretching for dancers. Resource Paper. International Association of Dance Medicine and Science. 2011. Available here.

2. Sefcovic N. First aid for dancers. Resource paper. International Association of Dance Medicine and Science. 2010. Available here.