Introducing the knee: Anatomy and biomechanics

Authors: Elsa Urmston and Jonathan George on behalf of the IADMS Education Committee

As dancers, educators and clinicians, we know that knees cope with a lot! Over the last decade or so, the demands placed on the dancer’s body has increased exponentially and ever more complexly. Acrobatic movement is becoming evident and the effect to the joints of the limbs can often mean greater incidence of injury. As Liane Simmel points out “pirouettes on the knees, knee drops, and even a plié in fourth position require particular leg stability and optimal mobility in the knee.”1 In reviewing the literature, Russell2 identifies the lower extremity to repeatedly be the most commonly injured region of the body amongst dancers.

The knee joint is hugely complex and as Teitz (in Solomon et al, 2005)3 explain there is no bony stability in its structure. A modified hinge joint, the knee comprises articulations between the femur and tibia, and the patella and femur, held together by a fibrous capsule and connected via a network of ligaments. It’s this lack of potential stability which makes the knee prone to injury, often through misalignment and poor mechanics, although as well through sudden trauma or overuse. Over the next couple of weeks we have a series of posts which focus on the knee; today we zone in on the structure, anatomy and mechanics of the knee itself. Part 2 provides an overview of common knee injuries amongst dancing populations, and in Part 3 we focus on two case studies of young men who have experienced knee issues during their training and have been successfully rehabilitated to class and performance via a joined-up clinical and educative rehab program.

The tibio-femoral joint is a hinge joint, capable of flexion (bending) and extension (straightening). The screw-home mechanism allows the knee to slightly internally and externally rotate too. During the last 30° of knee extension, the tibia (open-chain movement such as rond de jambe en l’air) or femur (closed-chain movements such as ascending from a demi-plié) must externally or internally rotate respectively by about 10°. This determines the knee as a modified hinge joint. You can see Rosalie O’Connor from American Ballet Theater demonstrating the screw-home mechanism in a rond de jambe action here!

The patellar-femoral joint serves to heighten stability in the joint. The patella (knee cap) is a sesamoid bone which sits in the quadriceps muscle, and during flexion and extension undergoes complex gliding movements. The fairly unanimous consensus as to the function of the patella is to effectively increase the movement arm of the patella tendon about the tibio-femoral joint, thereby magnifying the movement and force of the quadriceps muscle group about the knee.4

The stability offered by the joint capsule is complemented by numerous, strong ligaments and more than any other joint in the body, these ligaments are vital in guiding the aligned movements of the bones as they come together to form the joint. Yet, they are arranged in such a way that the stability is not always constant; some remain taut to ensure stability when the knee is extended and others slacken to ensure mobility when the knee is flexed5.

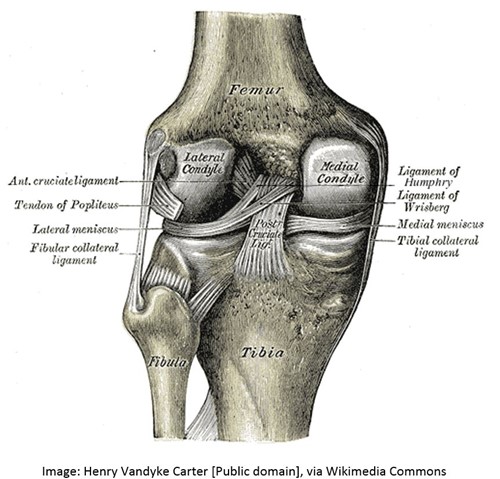

The medial and lateral collateral ligaments The collateral ligaments are located on either side of the knee joint (collateral means side by side). The medial collateral ligament – the one on the inside of the knee – is taut in knee extension and external rotation. It controls the knee if the knee rotates inwards and in fact when the knee bends in a demi-plie, it controls approximately 80% of the medial stress on the knee (Besier et al, 2001)6. The lateral collateral ligament – located on the outside of the knee – becomes taut with knee extension and provides lateral stability to the knee. It controls approximately 70% of the lateral stress of the knee for example when the knees bow out on flexion and cause the feet to roll outwards (Besier et al).

The cruciate ligaments The cruciate ligaments join the tibia and femur to one another within the internal structure of the knee. The cruciate ligaments prevent any forward/ backward motion of the femur and tibia in relation to one another. The anterior cruciate ligament also has another role in aiding rotation of the knee and controlling hyperextension in the joint. It also plays a role when deceleration from jumping, floor work and quick changes of direction are required. It is now also widely accepted that the anterior cruciate ligament provides up to 40% of medial knee stability7.

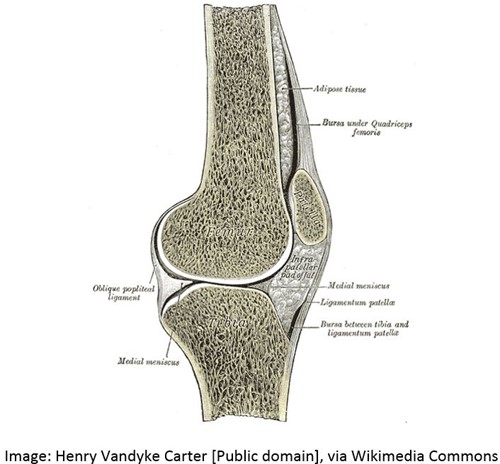

The menisci The medial and lateral meniscus are two cartilaginous discs which sit on the tibia and deepen the articular surface of the knee joint – they provide a kind of collar in which the bony ends of the femur sit, thereby improving the congruency and stability of the knee joint. They assist with shock absorption and help to friction thus aiding smooth knee movement. The menisci are critical in the production of synovial fluid-‘the oil’- around the knee joint.

Bursae The knee has the most extensive distribution of bursae in the body. More than 20 bursae are thought to be within the knee joint, with the primary role of reducing friction amongst the structures of the knee joint. Many are located around the patella to aid its gliding function within the muscle and over the top of the joint itself.

Iliotibial Band The iliotibial band is an adaptation of erect posture and provides key lateral support to the knee and hip; it runs down the side of the upper leg from the rim of the pelvis, to the outer edge of the femur and tibia.

This super video really provides a great introduction to the anatomy and ligament structure of the knee joint – take a look!

The musculature As with the skeletal anatomy of the knee, the muscles which act on the knee are complex! Because the muscles of the thigh also act on the hips, they often have a dual purpose –hip movement is included in brackets for ease of understanding here! We have provided a simple table of the main muscles which act on the knee to produce movement.

|

Muscle |

Action |

|

Anterior/ front of the thigh |

|

|

Rectus femoris |

Knee extension (hip flexion) |

|

Vastus medialis |

Knee extension |

|

Vastus intermedius |

Knee extension |

|

Vastus lateralis |

Knee extension |

|

Sartorius |

Knee flexion (hip flexion, hip abduction and hip external rotation) |

|

Posterior/ back of the thigh |

|

|

Biceps femoris |

Knee flexion and external rotation (hip extension and hip external rotation) |

|

Semitendinosus |

Knee flexion and internal rotation (hip extension and hip internal rotation) |

|

Semimembranosus |

Knee flexion and internal rotation (hip extension and hip internal rotation) |

|

Popliteus |

External rotation of femur when foot fixed; internal rotation of tibia when foot free |

|

Medial surface of thigh |

|

|

Gracilis |

Knee flexion (hip adduction and hip flexion) |

|

Posterior/ back of calf |

|

|

Gastrocnemius |

Knee flexion (ankle plantarflexion (pointing)) |

As you can see muscles often have more than one role in creating the movement of the limbs – we separate them out to learn about them, but of course they should be seen in their entirety to understand the complexity of the muscular system. This video really helps us to see the wholeness of this system but understand each individual muscle’s location in relation to each other – take a look.

Video no longer available.

References

1. Simmel, L. Alignment of the leg and its impact on the dancer's knee: Clips from the 2014 Annual Meeting

2. Russell, J. Preventing dance injuries: Current perspectives, Journal of Sports Medicine, 4, 199-210.

3. Solomon, R., Solomon, J. & Cerny Minton, S. Preventing Dance Injuries. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics, 2005.

4. DeFrate LE, Nha KW, Papannagari R, Moses JM, Gill TJ, et al. The biomechanical function of the patellar tendon during in-vivo weight-bearing flexion. Journal of Biomechanics 40:1716–1722, 2007.

5. Clippinger, K. Dance anatomy and kinesiology. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics, 2016.

6. Besier, TF., Lloyd, DG., Cochrane, JL. and Ackland. TR. External loading of the knee joint during running and cutting maneuvers. Medicine and science in sports and exercise33, no. 7:1168-1175, 2001.

7. Quatman CE, Kiapour AM, Demetropoulos CK, et al. Preferential loading of the ACL compared with the MCL during landing: a novel in sim approach yields the multiplanar mechanism of dynamic valgus during ACL injuries. American Journal of Sports Medicine, 42:177–186, 2014.

More information about the knee’s structure can be found in a variety of dance specific dance anatomy, kinesiology and safe practice books.

Elsa Urmston is the Centre for Advanced Training Manager at DanceEast, Ipswich, UK as well as Chair of the IADMS Education Committee and a member of the One Dance UK Expert Panel for Children and Young People. Jonathan George is a Chartered Physiotherapist at the DanceEast Centre for Advanced Training.