The female athlete triad in college dance students: Video from the 2014 Annual Meeting

Presented by: Amy Avery, BFA, MS, and Jane Baas, MA, MFA

IADMS Avery Baas from Steven Karageanes on Vimeo.

Diet and exercise is an important factor in addressing the health related problems of the estimated sixty seven percent of American adults who are overweight or obese.1 However, diet and exercise can also become a potential problem when mixed with a strong desire to become or maintain a very thin physique. Eating disorders can result from these desires, where harmful behaviors are used to lose weight or maintain a thin appearance.2 When taken to the extreme, the practice of excessive calorie restriction and expenditure can have severe health implications.3

The Female Athlete Triad (Triad) can result from disordered eating patterns and can have severe health consequences.4 The Triad is an interrelated problem and includes three syndromes:

1. abnormal dieting behaviors include restrictive eating, fasting, using diet pills, diuretics, enemas, overeating, binging and purging,5

2. amenorrhea, is characterized as the loss of menstruation, and 6

3. osteopenia or osteoporosis, is known as a decrease of bone mineral density.

The Triad can affect the entire body and mind in ways such as:

- a reduction in speed, endurance and strength.7

- fluid and electrolyte imbalances, with depleted muscle glycogen stores and blood glucose which can increase risk of injury. 8

- a higher incidence of infection, anemia, and electrolyte disturbances; impaired healing, cardiovascular differences, osteoporosis and endocrine conditions. 8 Without the production of estrogen, bone health can be compromised leading to increased occurrence of injuries and osteoporosis.

Without the proper intervention, the consequences of the Triad can be as simple as the loss of participation in physical activity or as severe as emaciation or death. 2,3 What may begin as a simple diet can lead to a psychological disorder, with eating disorders having the highest mortality rate of all mental illnesses.9

The occurrence of the Triad is a growing concern among populations, such as athletics, who focus on body image and body weight . 4 This population includes dancers. Research has indicated the figure to be as high as 60% or greater for athletes in particular sporting events. 10 Historically, having a thin physique has been essential for consideration in the dance world. Unfortunately, this can encourage eating disorders that are associated with the Triad. 11 The prevalence is unknown in college dancers. However, it is known to be higher in the dancer population due to collective pressures to maintain a thin body. 12 It is a common occurrence for dancers to limit their food intake to meet the demands of professional expectations of body image. Weight control is influenced by aesthetic considerations and body image.8 Much has been written concerning eating disorders in dancers. 5,8,12-15 However, few studies have been conducted regarding the Female Athlete Triad and the premature occurrence of osteoporosis.16,17

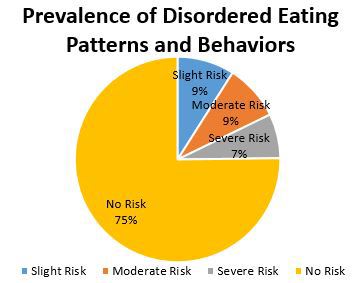

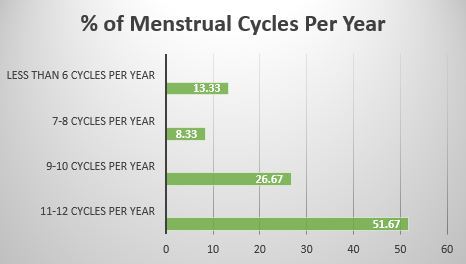

The purpose of this pilot study was to discover the prevalence of the Female Athlete Triad in college dance majors and minors. An anonymous survey was used to collect data from the current female dancers at an American university to determine if a relationship existed between injuries and eating disorders. Sixty female dancers participated in the survey that included a combination of questions extracted from the Eating Attitudes Test-26 (EAT-26) and the Pre-Participation Evaluation from the Female Athlete Triad Coalition. Findings indicated that 25% of participants could be classified as being in the symptomatic range for disordered eating patterns and behaviors; 48% stated the absence of a monthly menstrual cycle; and 16.67% had sustained stress fractures.

Dancers with a higher eating disorder attitude tended to have more injuries. Further, the sample population had disordered eating patterns and that a relationship existed among the Female Athlete Triad symptoms. In addition, more educational resources should be implemented in dance courses, along with an increase in seminars, town meetings, and counselling services addressing the consequences of eating disorders.

A Need for Education

In 1998, the American College of Sports Medicine advised detailed approaches be established to identify, prevent and treat this syndrome. These strategies included education about the Triad for a wide range of individuals including teachers, choreographers, directors, coaches, trainers, administrators, health care providers, parents and the dancers/athletes themselves. Identifying individuals who may be at risk is especially difficult in the dance population. In a field where a preoccupation with weight and disordered eating is considered "normal," how can we determine when “normal” becomes excessive? Becoming familiar with the signs and symptoms may help increase the prevention of a full blown eating disorder. It is recommended by the NCAA that those who work with dancers and the students themselves need to be aware of the risk factors and symptoms. Being aware of the situation is the first step in changing behavior. A teacher or a coach can be influential in providing students and staff with the education they need to decrease the risk of Disordered Eating and the Triad. Instructors must promote intelligent knowledge to their students and be healthy role models for their students.

Promoting healthy choices is crucial to the wellness of their dancers. Robson and Chertoff 18 make the following recommendations:

- Encourage positive attitudes and healthy bodies;

- Provide information regarding calorie consumption and energy expenditure;

- Raise awareness regarding adequate nutrition and bone health;

- Be mindful of early signs of the female athlete triad;

- Advise vulnerable dancers to seek proper assistance;

- Insist on regular medical check-ups;

- Create strategies to develop ideal health and wellness resources for dancers. Current research indicates a need for additional resources, education and information for dancers of all ages. This was especially true for dancers in a serious training facility.

References

1. Center for Disease Control/National Center for Health Statistics. (2009). Fast stats: Overweight prevalence. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/overwt.htm.

2. American College of Sports Medicine. (1998). Position stand, the female athlete triad. Journal of Dance Medicine & Science, 2(1).

3. Hobart, A. & Smucker, D. (2000). The female athlete triad. American Family Physician. Retrieved from http://www.aafp.org/afp/2000/0601/p3357.html

4. Reinking, M., & Alexander, L. (2005). Prevalence of disordered-eating behaviors in undergraduate female collegiate athletes and nonathletes. Journal of Athletic Training, 40(1), 47-51. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1088345/.

5. Sonnenberg, J. (1998). Etiology, diagnosis, and early intervention for eating disorders. Journal of Dance Medicine & Science, 2(1).

6. Sherman, R. & Thompson, R. (n.d.) Managing the female athlete triad. NCAA Coaches Handbook. Retrieved from htttp://www.princeton.edu/uhs/pdfs/NCAA%20 Managing%20the%20Female%20Athlete%20Triad.pdf

7. Williams, N. (1998). Reproductive function and low energy availability in exercising females, a review of clinical and hormonal effects. Journal of Dance Medicine & Science, 2(1).

8. Culnane, C., & Deutsch, D. (1998). Dancer disordered eating: Comparison of disordered eating behavior and nutritional status among female dancers. Journal of Dance Medicine & Science, 2(3), 95-100.

9. Sullivan, P.F. (1995). Mortality of anorexia nervosa. American Journal of Psychiatry. 152(7), 1073-1074.

10. Kenney, W., Wilmore, J., Costill, D. (2012). Physiology of Sport and Exercise. Champaign, IL. Human Kinetics, (5th ed).

11. The challenge of the adolescent dancer. (2000) International Association for Dance Medicine & Science. http://www.iadms.org/?1

12. Vincent, L. (1998). Disordered eating, confronting the dance aesthetic. Journal of Dance Medicine & Science, 2(1), 4-5.

13. Glace, B. (2004). Recognizing eating disorders. Journal of Dance Medicine & Science, 8(1), 19-25.

14. Ringham, R., Klump, K., Kaye, W., Libman, S., Stowe, S. & Marcus, M. (2006). Eating disorder symptomatology among ballet dancers. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 39(6), 503-8. DOI: 10.1002/eat20299.

15. Robson, B. (2002). Disordered eating in high school dance students: Some practical considerations. Journal of Dance Medicine & Science, 6(1).

16. Torstveit, M., & Sundgot-Borgen, J. (2005). The female athlete triad: Are elite athletes at increased risk? Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise. 37(2), 184-193.

17. Myszkewcyz, L. & Koutekakis, Y. (1998). Injuries, amenorrhea and osteoporosis in active females. Journal Dance Medicine & Science, 2(3) 88-94.

18. Bone health and female dancers; physical and nutritional guidelines. (2008) International Association for Dance Medicine & Science. http://www.iadms.org/?212