Caring for muscle strains demystified!

Author: Meredith Butulis, DPT, ACSM HFS

Welcome to our three part series on muscle, ligament, and bone injuries. We will explore some common myths, and how you can use current evidence to efficiently return to performance. This month, we will begin with muscular injuries.

“I strained my hamstring three months ago!”

“Why does it take so long to heal?”

“I’ve done everything from stretching to massage and I keep losing flexibility!”

As dancers, teachers, or allied health professionals, we’ve likely experienced or witnessed these self-diagnosed and self-treated muscle strains.

What are some essential pearls that the dancer, teacher, and allied health provider need to know when it comes to caring for muscular injuries?

Myth # 1: A muscle strain is the cause of the motion loss. Fact: Muscle strains are quite prevalent in dance and sport injury. 1,2 In addition to muscle spasm and tension that can follow a strain, structures that can limit range of motion include the joint capsule, ligamentous or myofascial adhesion, joint swelling, bone structure, neural tension, and dysfunction in how segments of the body work together. 3,4 It is common to have multiple structures limiting range of motion, even if there was a specific incident that seemed to cause the limitation. 1,3 Resolving the range of motion loss depends on a correct assessment of the entire kinetic chain.1,4,5,6, 7

Example: A dancer presents to an allied health provider; over the past month, she notes pain at the top of her left hamstring and progressive motion loss with stretching into left leg forward splits. She has received several sessions of hamstring soft tissue work without improvement. She has been working on back walkovers and back bends, but you find that she does not have the thoracic and shoulder motion for proper alignment of the shoulders over the wrists. You find that this has led to segmental dysfunction of the entire thoracolumbar spine. The solution to restoring this dancer’s left splits lies in restoring proper mobility of the spine and proper alignment of the shoulders over wrists in performing her bridge and back walkover skills.

This case illustrates the importance of assessing the performer’s skill specific alignment throughout the kinetic chain when formulating a treatment plan. It also illustrates that range of motion loss may present as muscular pain, but the cause may not be a muscular strain.

Myth #2: Muscle strains should typically be treated by self-prescribed stretches and fascia release.

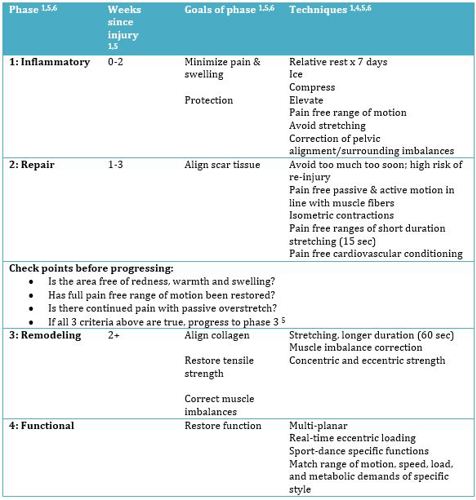

Fact: All tissues progress through healing phases. Current evidence supports matching rehabilitation strategies to healing phases. 1,5,6

Myth #3: After a muscle strain, a dancer should be back to full performance ability within 1-2 weeks.

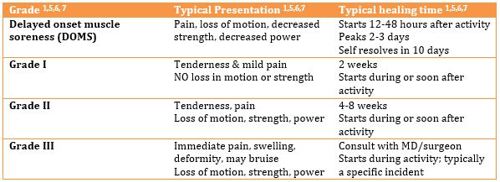

Fact: There are different types of muscle strains. Correct identification and proper early treatment can help manage time frame expectations.

Dancers, however, often do not rest or seek medical care.6 They also often take up to 32-50 weeks to return to premorbid dance levels after hamstring muscle strains.6 This prolonged recovery period is possibly due to lack of early proper treatment and premature return to activity.6 Additionally, re-injury rates can be quite high; the hamstring re-injury rate within one year is 34%.1

As we can see, seeking medical evaluation (even for a minor strain) could help dancers develop a proper plan of care to help with efficient return to performance.

Concluding thoughts:

Now that we’ve explored muscle strains, myths, and current recommendations in treatment, what will your actions be next time you suspect a muscle strain?

Meredith Butulis, DPT, MSPT, CIMT, ACSM HFS, NASM CPT, CES, PES, BB Pilates is a dance-specialized Physical Therapist, Personal Trainer, Pilates Instructor, and dance performer. With over 15 years of experience, she is based in Minneapolis, MN at Twin Cities Orthopedics and the Minnesota Dance Medicine Foundation.

References

1. Foglia A, Bitocchi M, Gervasi M, Secchiari G, Cacchio A. Conservative Treatment of Muscle Injuries: From Scientific Evidence to Clinical Practice. In: Bisciotti GN (Eds) Muscle Injuries in Sport Medicine, InTech, 2013. Available here.

2. Roberts KJ, Nelson NG, McKenzie L. Dance-related injuries in children and adolescents treated in US emergency departments in 1991-2007. J Phys Act Health. 2013; 10(2): 143–150.

3. Konin JG, Harrelson GL, Leaver-Dunn D. Range of motion and flexibility. In: Andrews, Harrison, Wilk (Eds) Physical Rehabilitation of the Injured Athlete, 3rd Ed, Philadelphia, PA: Saunders, 2004, pp. 129-156.

4. Lee D, Lee LJ. The role of the pelvis in hamstring injuries and posterior thigh pain. In Touch. 2009; 127

5. Page P. Pathophysiology of acute exercise-induced muscular injury: clinical implications. Journal of Athletic Training. 1995; 30(1): 29-34

6. Deleget A. Overview of thigh injuries in dance. Journal of Dance Medicine & Science. 2010; 14(3): 97-102.

7. Tiidus PM, Ed. Skeletal muscle damage and repair. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics. 2010.