Stretching the Point: Part 1

Author: Maggie Lorraine on behalf of the IADMS Education Committee

Learning how to bend the knees and point the feet may be the first movements that dance students learn. It is sobering to consider that both of these movements are potentially harmful if not executed correctly and practiced in perfect alignment. Experienced teachers of children and young people often notice that by encouraging students to “stretch” their feet rather than “point”, they are less likely to crunch their toes. Crunching results in a “shortened” line of the foot. On the other hand, “stretching” encourages the students to lengthen the leg through to the ankle and arch of the foot. Anatomically speaking we are talking here about plantarflexion of the ankle of course, although this actual term is seldom used in a teaching context.

The pointed or stretched foot is the image that we so closely identify with classical ballet and arguably the control of the stretched foot whilst dancing is one of the skills that may take the longest to master. It requires repetition throughout the dancers’ training to ensure sound alignment. When teaching young children to dance it is important to consider the bone development of the body, which is called ossification. The completion of growth in a tubular (long) bone is indicated by the fusion or closure of the epiphyses (growth plates), located at each end of the long bone. The long bones of the feet are the metatarsals – full anatomical information about the foot is available in previous blog posts here. The final epiphysis to close does so at an average age of 16 years in boys and 14 years in girls (1). Of course, dancing can place added stress on growing bones and negligent dance training may also affect the development of the bony structures - repetitive trauma in training and increased impact due to poor biomechanical alignment can cause the epiphyseal plate to widen, rather than close (2).

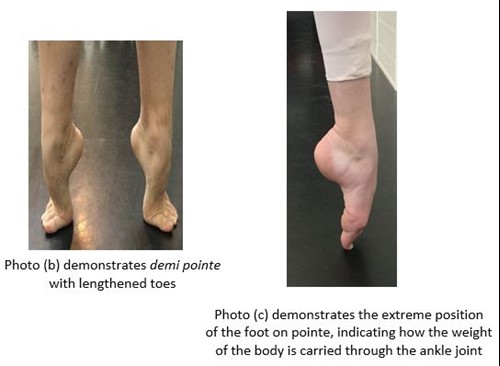

It is acknowledged that foot and ankle injuries are the most prevalent injuries in classical ballet in both the student and professional population (3). The extreme position of the foot and ankle when dancing on demi pointe, (see illustration b) where the ankle is in full plantarflexion, the body weight is distributed on the ball of the foot, or en pointe, where the dancer is on the tips of her toes (see illustration c), the weight of the body is carried through the ankle joint, and the longitudinal axis of the foot may put the dancer at risk of injury. Poor training, alignment, and faulty technique are all contributing factors to injury. Dancers, like athletes, are prone to common overuse injuries but they are also vulnerable to unique injuries, due to the extreme demands of ballet.

Teaching students how to align their feet and ankles, avoiding the urge to sickle (invert) or fish or wing (evert) when stretching their feet, and also ensuring that they do not crunch their toes (in an attempt to achieve the illusion of a high arch) will hopefully assist the student in avoiding serious foot problems. These issues will be exacerbated when the dancer rises on demi or full pointe. The control of the ankle when rising in an aligned position is a strengthening action. However, when the ankle and foot is not aligned the action of weight bearing is potentially injurious.

Frequently students crunch their toes in an attempt to point their feet harder and consequently this action contracts the muscles of the foot causing the joints of the foot and ankle to compress. Unfortunately, due to the students wearing shoes, the teacher does not always notice this problem, and the repetitive action possibly results in weakness in the intrinsic foot muscles and overuse of the extrinsic foot muscles, though this reasoning needs to be investigated scientifically. The issue sets up a pattern in the use of the foot that results in the toes crunching both when rising on demi pointe. Strengthening the intrinsic foot muscles could potentially enable the middle joint of the toes to remain lengthened while stretching the foot. Research groups around the world are currently investigating just such possibilities and continually present their progress at annual IADMS conferences.

As teachers, we know that the habits that are developed in early training always affect the student in later years when greater complexity of training is introduced. Setting up the pattern amongst our students that they should strive to hold their feet evenly on the floor and keep their toes stretched out along the surface of the floor will help. While the feet are bearing the body’s weight they should be holding the ground at three points - one behind the back of the heel, and two in front of the heads of the first and fifth metatarsals. This triangle forms a base from which the muscles and soles of the feet can work to support the arch and align the feet. Potentially this will assist in the recruitment of the intrinsic foot muscles.

“The intrinsic muscles are like the “core” muscles of the foot. Because they are deep and don’t cross over too many joints, they can work well in stabilizing and protecting the arch and structures within the foot. If the foot intrinsic muscles are weak, the foot structures are more prone to increased stress and injury. Strengthening the intrinsic muscles of the foot is good for people with foot injuries and for those looking to prevent injury”(4).

Supporting the arches whilst standing all helps in ensuring strong, adaptable feet for dancing.

The extreme positions created when dancing on pointe are particularly hazardous if the body and foot are not physically ready to deal with the weight of the body on pointe. IADMS has produced a really useful guide to point readiness available here.

In conclusion movement habits practised in early training can have a profound effect on the young dancer’s development and their potential for injury. By laying the foundation of sound alignment the teacher will empower the student to achieve their goals with reduced potential for injury. Celia Sparger describes it well:

"It cannot be too strongly stressed that pointe work is the end result of slow and gradual training of the whole body, back, hips, thighs, legs, feet, co-ordination of movement and the 'placing' of the body, so that the weight is lifted upwards off the feet, with straight knees, perfect balance, with a perfect demi-pointe, and without any tendency on the part of the feet to sickle either in or out or the toes to curl or crunch. “

The IADMS Education Committee will post a follow up article describing possible foot and ankle conditions and injuries that may impact on the dancer written by Gabrielle Davidson who is the Physiotherapist of the Dance Department at the Victorian College of the Arts Secondary School.

Maggie Lorraine

Leading Teacher in Ballet at the Victorian College of the Arts Secondary School. Australia.

Member of the IADMS Education Committee

References

(1) Weiss, D., Rist, R. and Grossman, G. Guidelines for initiating pointe training. IADMS Resource Paper, 2009. Available here.

(2) Laor T, Wall EJ, Vu LP. Physeal widening in the knee due to stress injury in child athletes. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2006; 186(5): 1260–1264.

(3) Foot and Ankle Injuries in Dance. Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation Clinics of North America December 2006.

(4) Amy McDowell, P.T From ARC Physical Therapy Blog

Further resources

Common Foot and Ankle Ballet Injuries

Dancing Child: Foot Development and Proper Technique

Micheli, L. J., Sohn, R. S., & Solomon, R. (1985). Stress fractures of the second metatarsal involving Lisfranc's joint in ballet dancers. A new overuse injury of the foot. J Bone Joint Surg Am, 67(9), 1372-1375.

O'Malley, M. J., Hamilton, W. G., Munyak, J., & DeFranco, M. J. (1996). Stress fractures at the base of the second metatarsal in ballet dancers. Foot & ankle international, 17(2), 89-94.

Wiesler, E. R., Hunter, D. M., Martin, D. F., Curl, W. W., & Hoen, H. (1996). Ankle flexibility and injury patterns in dancers. The American journal of sports medicine, 24(6), 754-757.

Kadel, N. J. (2006). Foot and ankle injuries in dance. Physical medicine and rehabilitation clinics of North America, 17(4), 813-826.

O'Malley, M. J., Hamilton, W. G., Munyak, J., & DeFranco, M. J. (1996). Stress fractures at the base of the second metatarsal in ballet dancers. Foot & ankle international, 17(2), 89-94.