Bunions in Ballerinas: it’s not really the shoes!

Author: Megan Maddocks

I have bunions, two in fact. They were never a problem while I danced, but they got worse when I stopped. As a podiatrist, this made me curious about the relationship between pointe shoes and bunions (more accurately called hallux valgus). Below is a brief summary of a literature review I presented at the 2016 annual IADMS conference in Hong Kong, outlining some extrinsic risk factors unique to female ballet dancers.

Hallux valgus (HV) is a common1 and complex deformity2. Being particularly common to dancers 3–9, it is believed that dancing plays a role in the cause and development of HV 10–12, however much research suggests that dancing is not a likely cause of HV 11–13.

COMMON MISCONCEPTIONS

It has been shown that the average number of dancing hours per week 3,14, hours of pointe work per week 3,14, total years of doing pointe work3 and the age of starting pointe3 are not significantly associated with HV in the dancer 3. Also, the intensity of practice (professional vs recreational) is not predicting variable for HV 3 and an increased Beighton (hypermobility) score, which most dancers have, has not been associated with HV10.

HV is mostly related to anatomical hereditary factors and to incorrect technical execution, rather than to the amount of dancing hours, with or without pointe shoes. 3,14

TRAUMA

Apart from rupture of the medial ligament of the big toe joint (first metatarsophalangeal joint – 1st MTPJ)3,14 from an incorrect landing or unexpected accident, there is substantial microtrauma to the joint from the hard pointe shoe box15.

FOOTWEAR

Constrictive Footwear

There is currently not enough evidence to implicate footwear in the development of HV 1,16. HV has been reported in populations that don’t wear shoes 1,17.

Dance Footwear:

Ballet Flats

Ballet pumps are chosen to fit tighter and tighter as girls get older, eventually fitting more like a glove than a shoe18. They are fitted, like pointe shoes, when the foot is non-weight bearing and pointed 18, ignoring the fact that the foot expands on weight bearing, resulting in the toes being squished together and increasing the tension on the inside of the big toe joint (1st MTPJ).

The Pointe Shoe

The bottom end of the box (block), on which the dancers bear weight, is flat, whereas the pointed toes do not form a straight line, resulting in the longest toe, usually the big toe (hallux), supporting the majority of the body’s weight when en pointe19.

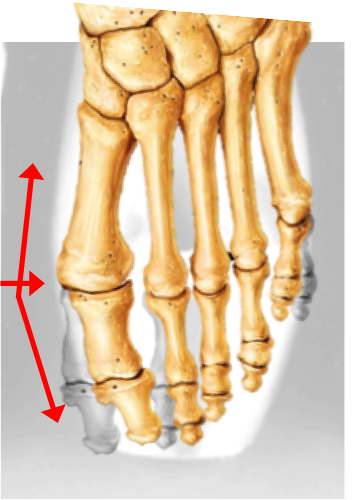

Inappropriate pointe shoe fit could exacerbate HV formation1,19: an overly narrow, short or soft toe box, results in the toes being squashed, increased tension on the big toe joint (1st MTPJ) and a general lack of support of the foot, (Fig.1). Proper pointe shoe fit is recommended to prevent or delay HV deformity, especially in the predisposed dancer1.

Fig. 1 – Foot structure change in a pointe shoe that is too narrow, created by M Maddocks

DANCE TECHNIQUE

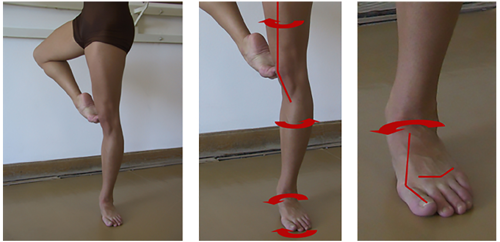

All turnout must be from the hip 6,18, however, it may be augmented at the knee, ankle, and foot 1,6,15,20. These forced turn out positions may result in pronation of the foot, with abduction of the big toe (points toward 2nd toe) and an increase valgus force on the joint 1,3,6,7,13–15,20, (Fig. 2). When the foot is frequently forced into exaggerated “turnout”, the supporting ligaments and tendons on the bottom and medial side of the foot and ankle may be lengthened and cause them to lose their ability to support the ankle joint and the arch of the foot 3,14,15,21.

Fig.2 – Hyperpronation / Rolling in : foot compensation for poor turnout at the hip, From Davenport1

It has been show that ankle plantarflexion is associated with HV3, and the average ankle plantarflexion (pointed foot) in professional female ballet dancers is 113°, which is more than twice the normal value of 50° 22. The combination of maximal ankle plantar flexion and an “over-pointed” foot may accelerate the progression of hallux valgus and exacerbate the symptoms 3.

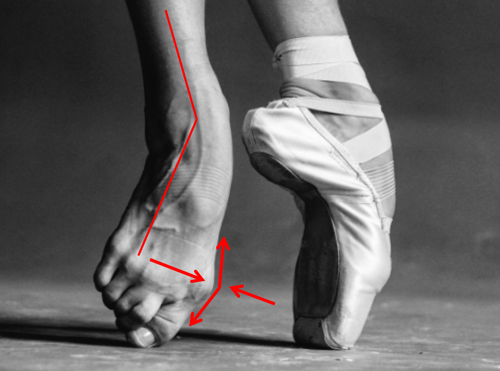

A small degree of ‘‘winging’’ (Fig. 3) can add to the aesthetic alignment of the line of the leg, however, an excess of pressure is applied through the first toe, particularly in a pronated foot 1,13. Hyperpronation or excessive “winging” of the foot while en pointe or demi-pointe may also result in microtrauma of the big toe joint (1st MTPJ)1.

Proper technique may prevent excessive loads on the big toe joint (1st MTPJ), which in turn may reduce the incidence of bunions.13

Fig. 3 – Winging: a technique fault in which the feet are forced outward or abducted at the ankles (Photographer: Darian Volkova)

Teacher Influence

Teachers should constantly strive to see that the leg and foot turn out as a unit from the hip18,21. Every effort should be made to control or avoid compensatory foot hyperpronation, as well as excessive winging, as it may increase the risk of hallux valgus development 1,6,18,21.

CONCLUSIONS

The unique positions and postures used in classical ballet are all potentially dangerous for the foot and leg6,18, with unique and increased forces through the big toe joint (1st MTPJ) and the foot while in extreme positions 1,3,5.

If that isn’t bad enough, the pointe shoe is the antithesis of everything that we, as podiatrists, know about footwear 18. Shoes for ballet dancers are not made for health 18, yet “dancer’s feet are the instruments on which their art depends”13.

Pointe shoes are definitely not protective of HV development 1, and it is almost impossible to prevent HV formation in an individual who is genetically predisposed18, but the evidence is not sufficient to conclude that pointe work causes HV1.

Dancers, like the rest of the population, are either prone to developing bunions or not 10,13,20. However, dancers are at high risk of developing hallux valgus as they have increased exposure to risk factors. Dancer’s at risk of developing HV need to be identified as early as possible and need to be managed conservatively with focus on good technique to reduce dance and non-dance biomechanical risk factors 3,6,13,23.

Megan Maddocks – IADMS Promotion Committee

Podiatrist – South Africa

REFERENCES

1. Davenport KL, Simmel L, Kadel N. Hallux Valgus in Dancers: a closer look at dance technique and its impact on dancers’ feet. J Danc Med Sci. 2014;18(2):86-93.

2. Dayton P, Feilmeier M, Kauwe M, Hirschi J. Relationship of frontal plane rotation of first metatarsal to proximal articular set angle and hallux alignment in patients undergoing tarsometatarsal arthrodesis for hallux abducto valgus: a case series and critical review of the literature. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2013;52(3):348-54. doi:10.1053/j.jfas.2013.01.006.

3. Steinberg N, Zeev A, Dar G, et al. The Association between Hallux Valgus and Proximal Joint Alignment in Young Female Dancers. Int J Sports Med. 2015;36:67-74.

4. Clippinger K. Dance Anatomy and Kinesiology.; 2007.

5. Miller H, Schneider HJ, Bronson JL, McLain D. A New Consideration in Athletic Injuries: THe Classical Ballet Dancer. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1975;(111):181-191.

6. Kravitz SR, Huber S, Murgia C, Fink KL, Shaffer M, Varela L. Biomechanical Study of Bunion Development and Stress Produced in Classical Ballet. 1Journal Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 1985;75(7):338-345.

7. Howse J. Disorders of the Great Toe in Dancers. Clin Sports Med. 1983;2(3):499-505.

8. Baxter DE. Treatment of Bunion Deformity in the Athlete. Orthop Clin North Am. 1994;25(1):33-39.

9. Schneider HJ, King AY, Bronson JL, Miller EH. Stress Injuries and Developmental Change of Lower Extremities in Ballet Dancers. Radiology. 1974;(113):627-632.

10. Prisk VR, Loughlin PF, Kennedy JG. Forefoot Injuries in Dancers. Clin Sports Med. 2008;27:305-320. doi:10.1016/j.csm.2007.12.005.

11. Einarsdottir H, Treoll S, Wykman A. Hallux Valgus in Ballet Dancers: A Myth? Foot Ankle Int. 1995;16(2):92-94.

12. Kennedy JG, Hodgkins CW, Colombier J, Guyette S, Hamilton WG. Foot and ankle injuries in dancers. Int Sport J. 2007;8(3):141-165.

13. Kennedy JG, Collumbier JA. Bunions in Dancers. Clin Sports Med. 2008;27:321-328. doi:10.1016/j.csm.2007.12.004.

14. Biz C, Favero L, Stecco C, Aldegheri R. Hypermobility of the first ray in ballet dancer. Muscles Ligaments Tendons J. 2012;2(4):282-288.

15. van Dijk C, Lim L, Poortman A, Al. E. Degenerative joint disease in female ballet dancers. Am J Sport Med. 1995;23(3):295-300.

16. Nix SE, Vicenzino BT, Collins NJ, Smith MD. Characteristics of foot structure and footwear associated with hallux valgus: A systematic review. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2012;20(10):1059-1074. doi:10.1016/j.joca.2012.06.007.

17. Zipfel B, Berger LR. Shod versus unshod: The emergence of forefoot pathology in modern humans? Foot. 2007;17:205-213. doi:10.1016/j.foot.2007.06.002.

18. Tax H. Ballet. In: Podopaediatrics. 2nd ed. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins; 1985:401-419.

19. Colucci LA, Klein DE. Development of an Innovative Pointe Shoe. Ergon Des. 2008.

20. Shrader KE. Biomechanical evaluation of the Dancer. Orthop Phys Ther Clin North Am. 1996;5(4):455-475.

21. Ahonen J. Biomechanics ofthe Foot in Dance: A Literature Review. 2Journal Danc Med Sci. 2008;12(3):99-108.

22. Russell J a, Shave RM, Kruse DW, Koutedakis Y, Wyon M a. Ankle and foot contributions to extreme plantar- and dorsiflexion in female ballet dancers. Foot ankle Int / Am Orthop Foot Ankle Soc [and] Swiss Foot Ankle Soc. 2011;32(2):183-188. doi:10.3113/FAI.2011.0183.

23. Weiss DS, Rist RA, Grossman G, Ed M. When Can I Start Pointe Work? Guidelines for Initiating Pointe Training. J Danc Med Sci. 2009;133:90-92.