Mental Imagery and Creativity

Authors: Klara Łucznik and Rebecca Weber on behalf of the IADMS Dance Educators' Committee

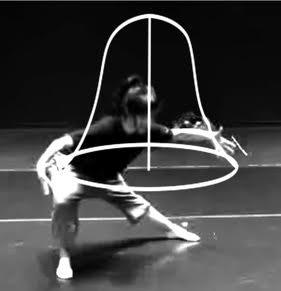

Just like dancers practice physical skills in their technique classes, so too can we practice mental skills. Though we often think of imagery as creating a ‘picture’ in our mind’s eye, imagery is the ability to create mental constructions of any sort--including visual imagery, sounds, movement, emotional content, spatial concepts, or language. These constructions are all forms of mental imagery. Mental imagery is widely used in choreographic practices in contemporary dance, including by artists like Wayne McGregor, William Forsythe, Hagit Yakira, and others. In such approaches, dancers engage in a variety of sensory modalities as a source of inspiration. They might visually imagine an object, spatial shape, or even entire landscape and then transform it into a particular quality, shape, or pathway of moving. Using auditory imagery, they might imagine the music, rhythm, or sounds that influence their movement choices. They might even create a mental image of an emotion or a bodily sensation, like moving through the ocean’s waves or rolling a small ball inside their body. Having created the image, they may transform it into movement or composed phrase (May et al., 2011).

Image: A Wayne McGregor|Random Dance dancer imagines moving a heavy bell around

Image: A Wayne McGregor|Random Dance dancer imagines moving a heavy bell around

(courtesy David Kirsh)

Many dance instructors likewise use imagery as a way to refine students’ skills, adding texture or quality to movement’s execution. Indeed, several branches of somatic practice are designed to affect awareness, alignment, or performance through imagery, such as Bartenieff Fundamentals, Ideokinesis, the Franklin Method, and embodied anatomy practices. Research shows that kinaesthetic and somatic imagery play a role in motor learning (Arandale et al., 2014) and have been applied to improve sport performance (Murphy, 1990). You may have even heard of the ‘mental rehearsal’ often encouraged in athletes. A considerable amount of research has shown that imagery and mental practice can enhance motor performance (Krasnow et al., 1997: 47).

Mental imagery comes in many forms, not just kinaesthetic or somatic. We can control the forms of imagery we use. In moving the focus of our attention around the imagery spectrum, we may engage in ‘polysensory imaging’ (Root-Bernstein & Root-Bernstein, 1999). And by mindfully selecting the forms of imagery we engage in practice, our imagery skills can be learned and improved.

Some research suggests that creative thinking can likewise be scaled, or increased with practice. One way to start practicing thinking creatively is through increasing our awareness of the types of forms of mental imagery that we engage with in creative practice. Though meta-analysis has indicated weak but significant correlations between mental imagery and creativity (LeBoutellier & Marks, 2010), it has been proposed that meta-cognition -- our awareness of our mental imagery skills and habits -- can be honed to help us avoid habitual responses when attempting to innovate, and preliminary research with dancers supports this proposition (deLahunta, Clarke & Barnard, 2011; May et al, 2011). Dancers in one study (May et al, 2011) even reported that such metacognition, or reflecting on their own mental habits during movement creation, allowed for more variation in the movement they generated. This increase in variation was achieved by consciously choosing a less-frequently used form of imagery, for example one might opt for using sound as an inspiration rather than kinaesthetic imagery. One project examining the effects of training metacognitive awareness is the In the Dancer’s Mind project.

In the Dancer's Mind - Creative Imagery Training

Image: Creative imagination workshop at Plymouth University.

Photos: L. Clements, B. Weber and K. Łucznik

In The Dancer’s Mind is a longitudinal and cross-sectional research project into creativity, novelty, and the imagination, funded by the Leverhulme Trust and being undertaken by Plymouth University, Trinity Laban Conservatoire of Music and Dance, and Coventry University. The project is testing whether training dance students in this metacognitive awareness of their use of imagery improves their ability to make creative choreography. The research compares two cohorts of dancers’ creativity levels at the start of their undergraduate studies and a year later, with one cohort being given training in recognising the forms of mental imagery and their own mental habits when using them.

This intervention was delivered by university dance teachers who used a creative imagery and movement toolkit that includes a teacher’s guide, a course pack, lesson plans, and set of workshop materials, which you can download from www.dancersmind.org.uk.

The course comprises 37 exercises, covering six training ‘targets’ that explore and train different modalities of imagery, principles for transforming imagery, and its application for movement creation. Each topic is supported with a theoretical introduction in the form of a short video-lecture. Here you can watch the general introduction to this programme:

The course pack includes a variety of exercises, delivered following the video lecture. The first of these are activities that develop creative imagery through mental training. In these exercises, dancers can explore how to apply principles for transforming imagery while sitting or lying down in stillness. For example, an exercise on visual imagery might ask you to imagine a hat. Then, an instructor may read a script encouraging you to mentally transform the hat by using the twelve imagery transformation principles--these are grouped as principles which change the whole, edit part, or modify the image in different ways.

Try it for yourself: imagine a hat. Can you change its scale and make it bigger (modify)? Can you personalise it--make it one of your favorite hats (change the whole)? Can you add a feather to it (edit part)?

Principles Cards (credits: In the Dancer’s Mind project)

Principles Cards (credits: In the Dancer’s Mind project)

This same exercise could be done on other forms of mental imagery, like sound. Such mental practice allows students to gain confidence in creative imagery.

Next, students are offered movement exercises, where these mental skills are applied to a movement task. These exercises explore how imagery might be use translate into physical ideas, movement qualities, and generation of dance material. Finally, discussion exercises allow the class to reflect on the experience and discuss with the class or in small groups.

These courses offer a flexible modular design, with suggested lesson plan options which adjust the length of the module or the time of individual classes to suit the needs of the particular group or course. These are outlined in a teachers’ guide that also introduces the general context for imagery use as a choreographic tool. All materials have detailed guidance but are also very flexible, so you can use them in the way you think they will be most beneficial for your practice.

Preliminary results shows that our imagery training successfully increases creativity of dance students, both by improving their creative thinking and advancing the use of imagery in their choreographic process. Teachers who used the In the Dancer’s Mind training programme as a part of their choreographic modules reported that the students’ engagement in creative exploration was raised, and they were able to stick with the task for longer. The effect of training was noticed beyond the choreographic practice modules, with impact on enhancing students’ choreologic analysis abilities and improvisational skills. Furthermore, the principles were found to be applicable beyond the imagery context. If you want to learn more about the project and results of the training programme, just visit the project’s website: www.dancersmind.org.uk.

Klara Łucznik, PhD., is a Researcher in a field of Dance Cognition and a part of interdisciplinary research group CogNovo at Plymouth University.

Rebecca Weber, MFA MA RSME is a PhD Candidate at Coventry University’s Centre for Dance Research, Director of Somanaut Dance, Co-Director of Project Trans(m)it, and an associate lecturer at the University of East London.

For further reading, have a look at these resources:

Andrade, J., May, J., Deeprose, C., Baugh, S.-J. and Ganis, G. (2014), Assessing vividness of mental imagery: The Plymouth Sensory Imagery Questionnaire. British Journal of Psychology, 105: 547–563.

Krasnow, D. H., Chatfield, S. J., Barr, S., Jensen, J. L., & Dufek, J. S. (1997), “Imagery and conditioning practices for dancers”, Dance Research Journal, 29, 43–64.

LeBoutellier, N. & Marks, D.F. (2010) “Mental imagery and creativity: a meta-analytic review study”, British Journal of Psychology, 945:1, 29-44.

May, J., Calvo-Merino, B., deLahunta, S., McGregor, W., Cusack, R., Owen, A. M., & Barnard, P. (2011) “Points in mental space”, Dance Research Journal, 29, 404–432.

Murphy, S. (1990), “Models of Imagery in Sport Psychology: A Review”, Journal of Mental Imagery, 14:3/4, 153-172.

Root-Bernstein, R. and Root-Bernstein, M. (1999), Sparks of Genius: The Thirteen Thinking Tools of the World’s Most Creative People, Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co.