Aging and range of motion for dancers: An introduction to a three-part series

Author: Janine Bryant on behalf of the IADMS Dance Educators’ Committee

The learning objectives of this article:

- To broadly understand the aging process and its impact on function and quality of life for dancers

- To understand how this information can help dancers age well and therefore affect career longevity

- To encourage dancers to create an awareness statement based on this information on how they can help themselves age well as a dancer-athlete

- To help dancers understand how how the very act of dancing puts them at an advantage over the aging process in some ways.

The process of aging affects all of the body systems. Aging causes loss in bone density, flexibility and range of motion (ROM). Women experiencing hormonal changes are especially are at risk as the loss of bone density can cause increased risk for fractures.4

Much of the available literature on aging includes information on quality of life (QOL) issues such as diminished mobility. 10 When mobility is limited due to an injury or medical condition, a vicious cycle ensues, resulting in increased pain, stiffness and further diminished mobility. For dancers, this process can be life altering, as age is often a determinant in participation levels. 10

Certain conditions are more prevalent as we age, such as osteoarthritis (OA). OA is the most common arthritis and is one of the main concerns with regards to mobility as changes in collagen could result in loss of joint function. This is usually more common in the 65+ age categories.5 With regards to low calcium and oestrogen levels, specifically on bone, there are two factors at work. A calcium-deficient diet coupled with decreased oestrogen levels can affect healthy bones in unhealthy ways, leading to osteoporotic bone. For dancers, a hard schedule coupled with fractures of built up osteophytes from OA, in addition to increased load from aesthetic demands and big ROMs, have a cumulative effect over time and can result in decreased ROM and increased pain. In terms of bone mass, females generally peak around age 30 and begin to decrease more rapidly than men, who peak around age 40 and begin to experience bone loss around age 45, although the decline is more gradual. 10

Dancer's Advantage: It should be noted that the activity of dancing as exercise improves bone health and can also increase muscle strength, coordination, and balance, leading to better overall health. Bone is living tissue that responds to exercise by becoming stronger. Women and men who exercise regularly generally achieve greater peak bone mass (maximum bone density and strength) than those who do not. 7,9

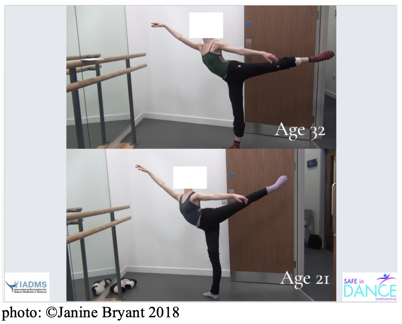

In the above photo, it is clear that the 21-year old dancer does in fact have greater ROM in the first arabesque. However, there are some problems with muscle recruitment and stabilization that the 32-year old dancer has worked out for herself. We can see the dancer on the top of the photo is more over her forefoot, is utilizing her standing quadricep muscles to stabilize, and has a more lifted and closed ribcage. As with many older elite professional dancers that I see in my studies, although they cannot make the ROMs that the younger dancers can, their shapes are more stable and less dependent on flexibility alone. All dancers have somatic challenges that they must surmount that, in the excitement and artistry of performance, is often not evident to the audience and these examples provided are no exception.

Dancer's Advantage: The photo is simply offered to encourage a dialogue that, although the aging dancer is often at a disadvantage in the youth-driven dance world, they can in fact offer a body knowledge that is oftentimes more thorough, hard-earned and worth valuing.

Aging Collagen and the Accumulation of Advanced Glycation End Products (AGEs)

Collagen is protein. Aside from water, collagen is the most plentiful substance in our bodies and is the building block for skin, tendons and bones. Over 90% of collagen in the body is comprised of Type 1 and 3 collagen. Collagen types that are commonly affected by the aging process likely to have an impact on dancer-athletes are collagen types 1, 2 and 3. Collagen types contain different proteins (amino acids) and these serve separate but often parallel purposes within the body. Types 1 and 3 support structures and elements of high-tensile strength, bone, skin, tendon, muscles, cornea, and walls of blood vessels. Type 2 collagen is comprised of the fluids and function that supports cartilaginous tissues and joints, as well as intervertebral disks (IVDs), vitreous bodies, and hyaline cartilage. 6,10

As collagen ages, skeletal muscle fibers decrease in mass (sarcopenia), tolerance for exercise decreases and there are higher rates of fatigue and decreased ability to thermoregulate. In addition, there is an impaired ability to recover from injuries. The cyclical response to this is often increased pain and a general decrease in elasticity and flexibility. 9

The loss of skeletal muscle elasticity can be correlated with the presence of advanced glycation end products (AGEs). Collagen becomes damaged when sugar and amino acid molecules bind together. The by-product of this process is oxidative in nature and causes AGEs to accumulate in cells. Accumulation of AGEs can wreak cellular havoc, and the increased oxidative stress results in chronic inflammation. 6,7

We consume AGEs mostly from food (specifically high-fat meats) cooked at high temperatures via dry heat, or processed foods, and absorb AGEs from tobacco smoke. Declined kidney function has also been implicated in the formation of AGEs and dancers with high blood sugar, familial history of such, or insulin resistance, could be at risk for an increased presence of AGEs. However, high levels of AGEs are found in many healthy older people as well as in those with chronic diseases. It is therefore unclear the degree this plays in human health and aging and so the current research remains inconclusive. The research does support the idea that a diet low in AGEs (one that avoids baking, grilling or frying food for long periods of time and at high temperatures) can in fact lower blood levels of AGEs, reduce insulin resistance and decrease markers for inflammation and oxidative stress. However, more research is needed to fully understand the effects of AGEs on the human body. 11

Dancer's Advantage: Aside from the mood and mind benefits, dancing can increase muscle fiber growth, and improve flexibility and balance, especially in populations over the age of 35, 7 possibly offering dancers some leverage over the aging process.

What should dancers think about with regards to aging well?

Intrinsic Factors: Dancers would benefit from knowing their genetics and family history, especially with regard to conditions such as diabetes, insulin resistance, arthritis, and other inflammatory responses. As well, dancers can think about their current hormonal status and age as fair markers to providing clues to their overall health status picture.

Extrinsic Factors: Dancers would benefit from safer training protocols from young ages and safer techniques to big ROMs. Factors such as quality of nutrition, amount of sleep, stress levels, and smoking can have a direct effect on how dancers age and can be controlled. Social support and networks have been found to have a positive effect on aging, as populations live longer, having and maintaining social connections is associated with mental wellbeing and a feeling of connectedness.

Above all, dancers should keep moving! The research supports that negative health outcomes are associated with impaired mobility and that health and wellbeing are enhanced through strategies that optimize mobility. 7,10

Based on the information provided in this article, dancers are encouraged to create an awareness statement supporting the idea of healthy aging and career longevity.

In the next article, we will discuss what the published literature says about aging and range of motion.

Janine Bryant, BFA, MA, SFHEA, PhD Candidate, is a Registered Provider and Quality Assessor for Safe in Dance International and International Education Advisor to The University of Wolverhampton, UK. She has presented her research on aging and range of motion in Brazil, UK, USA, and Finland. Janine is a guest speaker for The Royal Ballet School, UK and The University of the Arts, USA.

References

1. Wong KW, Leong JC, Chan MK, Luk KD, Lu WW. The flexion-extension profile of lumbar spine in 100 healthy volunteers. Spine. 2004; 29(15):1636-41.

2. Benjamin M, Toumi H, Ralphs JR, Bydder G, Best TM, Milz S. Where tendons and ligaments meet bone: attachment sites (‘entheses’) in relation to exercise and/or mechanical load. J Anat. 2006; 208(4):471–490.

3. Jackson AR, Gu WY. Transport properties of cartilaginous tissues. Curr Rheumatol Rev. 2009;5(1):40.

4. Papadakis M, Sapkas G, Papadopoulos EC, Katonis P. Pathophysiology and biomechanics of the aging spine. Open Orthop J. 2011; 5:335–342.

5. Ferguson SJ, Steffen T. Biomechanics of the aging spine. Eur Spine J. 2003; (Suppl 2):S97–S103.

6. Jaskelioff M, Muller FL, Paik JH, et al. Telomerase reactivation reverses tissue degeneration in aged telomerase-deficient mice. Nature. 2010;469(7328):102-6.

7. Hamerman D. Aging and the musculoskeletal system. Ann Rheum Dis. 1997; 56(10):578–585.

8. Rajasekaran S, Venkatadass K, Babu J, Ganesh K, Shetty AP. Pharmacological enhancement of disc diffusion and differentiation of healthy, ageing and degenerated discs: Results from in-vivo serial post-contrast MRI studies in 365 human lumbar discs. Eur Sp J. 2008;17(5):626-43.

9. Singh K, Masuda K, Thonar E, An H, Cs-Szabo G. Age-related changes in the extracellular matrix of nucleus pulposus and annulus fibrosus of human intervertebral disc. Spine. 2009;Vol. 34 (1):10-16.

10. Loeser RF. Age-Related Changes in the musculoskeletal system and the development of osteoarthritis. Clin Geriatr Med. 2010;26(3):371–386.

11. Chen, JH, Lin, X, Bu, C, & Zhang X. Role of advanced glycation end products in mobility and considerations in possible dietary and nutritional intervention strategies. Nutrition & metabolism. 2018;15:72.