Measuring a Pirouette: Tackling the challenge of quantifying dance

Author: Catherine Haber on behalf of the IADMS Dance Educators’ Committee

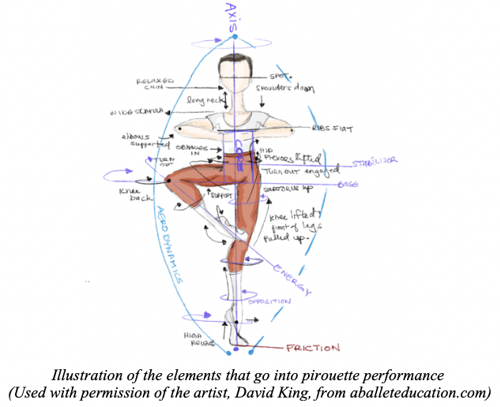

Pirouettes are incredibly challenging for dancers to perform, but also for scientists to study! As we heard from January’s post, physical principles – such as torque, force couples, angular acceleration, and conservation of angular momentum – can help us gain better insights into performance. However, beyond these principles, there are a multitude of crucial elements that go into the performance of a pirouette. The dancer must balance in a proper passé position, reach a high relevé on the supporting foot, hold the arms in first, engage the core, spot his head, and many more! With all these components to coordinate, what should the dancer focus on, and what should the scientist measure?

With a double Bachelors in Dance and Physics, I was thrilled to begin working as a research assistant during my Graduate studies to Dr. Andrea Schaerli, in her research of the influence of spotting on postural stability in the ballet rotations of pirouettes and fouettés. We recorded dancers in motion capture labs performing rotations, and I was eager to direct my knowledge in physics to my passion of dance. I calculated everything from the displacement of the supporting foot, the trajectory of the center of mass (COM), the velocity of the head spotting, the separation of the head, trunk, and pelvis coordination, and many more variables that triggered my interest. However, it quickly became overwhelming when I realized the magnitude of possibilities for analysis. The question became not only what should we measure, but also – at the end of the day – what measure is the most relevant and applicable to the dance population? How can we as researchers find meaningful outcome measures that most closely capture the dancer’s experience of performance?

In a day and age of great technological advances, movement can be measured in many ways - from 2D video analysis to 3D motion capture, force platforms and electromyography (EMG) measures of muscle activation, and even the direction of eye movements. Yet dance inherently relies on experiential and aesthetic variable that can be challenging to quantify. Studying dance thus calls for the creation and validation of dance-specific measures. Therefore, we performed two small studies to integrate dancers’ impressions of performance into our analysis.

The first of these two studies was a pilot study that aimed to validate a balance measure that best predicts the performance of pirouettes. To this end, eight intermediate dancers performed many pirouettes in our movement lab and rated their performance after each turn, while the researcher independently did the same. Followingly, we correlated the most predominantly used measures of pirouette performance in dance science research with the dancers’ and researcher’s impression of the turn.

Here, it was found that the dancers’ performance was highly correlated with the angular deviation of the pelvis center from vertical – that is, how far off the center of the pelvis is from the vertical line drawn up from the supporting toe. This follows previous findings of smaller angular deviations between the center of mass (COM) and a vertical line from the base of support (here, approximated at the supporting toe) during successful pirouettes. In our study, the dancers gave their turns higher performance ratings when their pelvis – rather than the COM – was closer to this vertical line. This was an interesting finding for two reasons. From a research perspective, the deviation of the pelvis was highly correlated to the deviation of the COM (with this ‘true center’ actually residing within the pelvis of these female dancers during the pirouette). This means that researchers could use the pelvis center as an economical approximation for the tediously calculated COM during pirouettes. From the perspective of the dancer, while it may be challenging to have a clear understanding of your ‘true center’ throughout dynamic movements, being in tune to where your pelvis is can be a good starting point for pirouettes.

A second interesting finding was that from the observers’ perspective, performance was best associated with the instantaneous axis of rotation – that is, the deviation of the best-fit line through the head, torso, and supporting leg, from vertical. The observer perceived better turns based on this holistic impression of verticality. Therefore, this pilot validated additional measures of pirouette performance that best represented the impression of the dancer and the observer.

In a second effort to incorporate dancers’ opinions into research, we performed a Delphi Method survey to gather expert opinions on the characteristics and uses of spotting. While many measures have been used to describe balance in pirouettes, little research has been done on spotting itself. Therefore, we asked professional ballet dancers, professional ballet teachers, and dance scientists to participate in a Delphi Method survey, bringing together expert opinions over iterative rounds to generate ideas and to evaluate levels of consensus. After three rounds of first brainstorming ideas, then rating agreement on the group’s ideas, and finally ranking the most important ideas, the consensus of the group was actually quite low in defining the most important characteristics and uses of spotting. However, a novel variety of topics were proposed. Building on the traditional suggestions of spotting for balance and reduction of dizziness, spotting was suggested to have further functionality for orientation, rhythm, and particularly in multiple turns.

The value of integrated expert opinions was quite apparent when it came to aspects of rhythm. When splitting the group into dance practitioners (teachers and dancers) and dance scientists, it appeared that the practitioners had a great affinity for topics relating to rhythm. In contrast, dance scientists tended to rank these topics relating to rhythm very low. This survey was thus able to bring new perspectives to the understanding of spotting that can serve as meaningful hypotheses for future movement-based research. As such, we performed a study last fall capturing professional dancers performing the multiple rotations of fouetté and a la secondé turns to examine exactly these proposed functionalities of spotting.

Elénore Guérineau, soloist from the Zurich Ballet, performing fouetté turns

with motion capture measures of her movement and Electrooculography (EOG)

measures tracking her eye movements for signs of dizziness.

(Used with permission of the dancer)

Analyzing dance from a scientific perspective can be a challenging feat. However, we must not forget why we are motivated to do such research: to help improve dancers’ performance! Particularly from the perspective of movement analysis where one can become fixated on degrees of difference or centimeters in jump height, the perception of the dancer must not be lost. Dance is an interdisciplinary, physical system yet to be fully analyzed. With collaborative efforts of the community of practitioners and researchers, we can determine comprehensive, dance-specific measures and methodologies to benefit the well-being and training of dancers.

Catherine Haber is a Graduate student, currently finishing a MAS in Dance Science and a MSc in Sport Science Research, and a research assistant to Dr. Andrea Schaerli at the Institute of Sport Science at the University of Bern, Switzerland.