Healthy Dancing for Every Body

Invited authors

Rebecca Barnstaple, Ph.D. candidate, York University, Toronto, Canada

Lucie Beaudry, Ph.D. candidate and assistant professor, Université du Québec à Montréal

Professor Sylvie Fortin, Université du Québec à Montréal

IADMS has recently expanded its mandate to include a focus on Dance for Health (DfH) with the aim to promote and validate dance as a life-long partner for health and well-being for all publics. The development of innovative research related to a variety of healthy dance practices is a key aspect of this initiative. In this brief report, we present core aspects behind the rationale for this new direction of IADMS, followed by a description of a substantial DfH research collaboration in Montreal, Québec, Canada, host city of IADMS 29th Annual Conference.

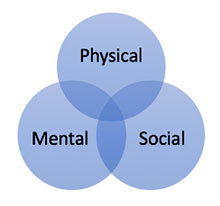

While dance is historically connected with healing in many cultures, medical and scientific interest in applications of dance within rehabilitation, therapy, health care and well-being are more recent, accompanied by an emerging body of research exploring the efficacy and mechanisms of dance-based interventions through a range of methods. These may be qualitative, quantitative, mixed, or art-based, reflecting the inherent complexity of dance as a holistic activity encompassing art, physicality, sociality, and environment – essential aspects of our humanness (Fortin, 2018). Clare Guss-West and Emily Jenkins in their blog post Introducing Dance for Health (DfH) suggest that “The joyful, social, creative and expressive elements of dance are perhaps the precise reasons for its efficacy within health contexts”[i], and the DfH roundtable in Helsinki identified a primary need for research addressing “dance beyond physical activity”. We could add that DfH explores dance beyond psychotherapeutic uses of dance/movement, associated with dance/movement therapy.

DfH initiatives are not presented as therapy, but nevertheless can offer many therapeutic benefits. Dance has the potential to act as an adaptive and widely-applicable health intervention that is multimodal both in delivery and benefits. Beyond physical activity, dance requires complex coordination of motor skills, cognitive strategies, affective and attentional resources, and aesthetic components. Cognitive tasks such as learning choreography (Bar and DeSouza 2016) or responding to cues that invite improvisational problem solving (Batson et al 2016) recruit distinct brain regions and neural networks, while partnered dance forms and exercises can involve complex social strategies such as mimicry (in mirroring), communicative responses (partnered improvisation), and learned roles or vocabulary (such as in tango or salsa).

Interoception, proprioception, and kinesthetic awareness are all heightened by dance, which can improve body image as well as fine and gross motor control (Muller-Pinget et al, 2012; Gose 2019). Dance is also a creative form of emotional expression, which may be enhanced by music. Entrainment, or action that is synchronous with external cues such as music, has been shown to modulate neural entrainment (Thaut 2006). Finally, dance makes use of space in specific ways that extend beyond exercise studies. These broad engagements of the situated nervous system through dance demonstrate its relevance for all bodies; thus IADMS has expanded its activities to be inclusive of anyone dancing. However, research on dance in the context of health interventions can be difficult due to the involvement of, and interactions between, many factors. Interdisciplinary collaborations blending the best tools of science with the nuanced approaches of humanities and the creativeness of the arts may be optimal for addressing the challenges involved in developing meaningful research on DfH.

An example of this is found in Quebec, Canada, where the project Audace (2018-2020) brings together 11 researchers with different backgrounds (dance, creative arts therapies, education, kinesiology, neuropsychology, rehabilitation and sociology[ii]). This highly interdisciplinary team demonstrates the challenges involved in negotiating a shared language to develop and assess interventions across various population groups: adult out-patient rehabilitation service users; healthy inactive community-based older adults; children with neuro-visual problems; ex-homeless women with mental health issues and addictions; adolescents with cerebral palsy; people with Parkinson’s disease. The inclusion of various approaches in DfH is an intentional effort on the part of project members to go beyond labels (such as dance therapy, adapted dance, expressive/arts therapy, creative dance, modified dance intervention, developmental dance, Laban-based dance, community dance, etc.) and to focus on complementary relationships rather than abstract stances. Presuming that the content and the pedagogy can vary greatly under the same label, or that different labels might present quite similar content and pedagogy, one objective of the research is to open and explore details within the “black box” of different interventions.

While looking for compelling evidence of the effects of dance for health, we want to better understand the “active ingredients” of dance-based interventions in terms of pedagogy and content. We also want to go beyond these laudable intentions by recognising that dance, across cultures, is fundamental to our embodiment as human beings, and aspects of movement experiences may evade complete description or sophisticated analysis. For these reasons, the Audace project will culminate with a “creative act” engaging all parties involved. Organized in partnership with the National Centre for Dance Therapy, this will be a multi-media event bringing together many artistic modalities (live dance demonstrations, videos, pictures, projections, etc.), highlighting the myriad approaches and applications within dance that influence health and well-being.

With its innovative interdisciplinary design, the Audace project does not seek to establish the competencies of an individual practitioner, or a single professional role, or a specific research method, but rather to explore the potential inherent in people from distinct professional backgrounds coming together to create a unified field of practice and research. The future lies in our ability to collaboratively encourage all bodies to explore the myriad ways in which dancing can contribute to experiencing health, well-being, artistry, and agency throughout the lifespan.

References

Bar RJ & DeSouza JFX. Tracking plasticity: Effects of long-term rehearsal in experts encoding music to movement. PLoS ONE 2016;11(1):p. e0147731

Batson G, Hugenschmidt CE, Soriano CT. Verbal Auditory Cueing of Improvisational Dance: A Proposed Method for Training Agency in Parkinson’s Disease. Frontiers in Neurology 2016;7(2):215-215.

Fortin, S. Tomorrow’s dance and health partnership: the need for a holistic view, Research in Dance Education 2018, 19:2, 152-166, DOI: 10.1080/14647893.2018.1463360

Gose, R. Extraordinary dance requires extraordinary motor learning. Journal of Dance Education, 19: 34–40, 2019 Copyright © National Dance Education Organization ISSN: 1529-0824 print / 2158-074X online DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/15290824.2017.1383611

Muller-Pinget S, Carrard I, Ybarra J, & Golay A (2012). Dance therapy improves self-body image among obese patients. Volume 89, Issue 3, December 2012, Pages 525-528. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2012.07.008

Thaut MH. Neural Basis of Rhythmic Timing Networks in the Human Brain. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. First published: 24 January 2006. https://doi.org/10.1196/annals.1284.044

[ii]Bonnie Swaine, Sylvie Fortin, Raymond Caroline, Duval Hélène, Lemay Martin, Lucie Beaudry, Louis Bherer, Guylaine Vaillancourt, Patricia McKinley, Frédérique Poncet, Sarah Berry