Nutrition Research should drive advice and practice: which nutrients should the dancer be updated on and why: Video from the 2014 Annual Meeting

Presented by: Jasmine Challis, BSc, RD

This blog looks at the information I presented at the 2013 IADMS conference in Seattle. It looks at an area where there is a lot of controversy and tries to steer a research based path to advise the dancer on current best practice considering the current evidence.

Dancers interested in making sure their food and fluid intake optimises their performance are faced with a huge amount of nutrition information in magazines, newspapers, the internet, blogs(!), TV and radio programmes, Twitter and other social media, plus that from teachers/colleagues/ peers/family and friends. It can take determination not to be drawn into believing the latest trend as to what is best. It is probably useful to remember that nutrition research changes knowledge slowly in almost every case, so if a claim sounds dramatic, it has probably been exaggerated or the actual information twisted to try and make a story.

When we think about nutrition we tend to think about energy, measured in either kcals (USA) or kjoules (Europe and Australia), which can come from carbohydrates and fats (and alcohol- though not relevant for training/performance), - and technically from protein. Although protein can be used as an energy source, it can’t then be used for its main roles in growth and repair so it’s not a viable option for most dancers. It is also the most expensive component of most meal plans so most dancers will have more of a challenge to take in enough protein to meet their needs than to have surplus to burn as a source of energy.

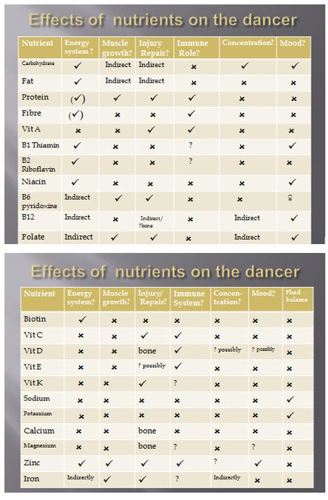

Moving on from energy we then need to consider the vast range of vitamins and minerals that humans, including and particularly dancers, need. There is ongoing research identifying new roles for established nutrients, such as Vitamin D having a role for a healthy immune system, as well as clarifying the roles of nutrients such as Vitamin E which we still don’t fully understand.

The tables below show the vitamins and minerals that are perhaps of most relevance to the dancer, and the body systems that are most important in dance and whether the nutrient may or may not be involved. Nutrition research is very challenging for a number of reasons. It is difficult to persuade people to keep to a fixed diet so that an experiment can be done to change just one food or nutrient; people do not all react the same; it may take a long time to see a difference, and all of this makes research very expensive and time consuming. Also, when trying to change a nutrient, unless it can be added to an existing part of your diet, for example adding folate to bread, then introducing more of one nutrient, means another typically must be reduced and this can impact your total energy intake which may in itself affect the results. Another problem is that large amounts of any nutrient is likely to do harm, and at extremely high intakes the body may process these nutrients differently compared to when taken in moderate amounts.

There is also a problem that anyone can call themselves a nutritionist – though the title ‘Dietitian’ or ‘Dietician’ is legally protected – so there are many ‘experts’ who are taking some evidence (at best), and advising people without having the depth of knowledge to give the best advice. Always remember that if it sounds too good to be true, it probably is. And that nutrition is almost never black and white, because of the simple reason that if you make a change you are most likely taking something out of your meal plan to put something else in. If you take out sweets and put in fruit, your energy level as well as your intake of vitamins and minerals may well be better overall, but if you were eating a lot of sweets you will need to put in a large amount of fruit which may upset your digestive system at least initially (you may adjust in time) and also be acidic for your teeth and result in some damage over time. So what sounds like a very good change may bring a less welcome effect.

Small gradual changes you can sustain are best – avoid making huge changes that take a lot of time and effort unless your starting meal plan really needs a complete overhaul and is causing you problems at the moment.

So, think about your food plan, be honest with yourself; if changes would be helpful introduce them gradually and make sure you can keep up the new plan, along with the benefits it will bring, before making further changes. If you can find foods that you enjoy and that help you achieve your nutrition goals that is going to make keeping to a meal plan easier!

Jasmine Challis, BSc, RD