Caring for bony injury demystified!

Author: Meredith Butulis, DPT, ACSM HFS

Welcome to Part Three of our three part series on muscle, ligament, and bone injuries. We will explore some common myths and how you can use current evidence to efficiently return to optimal performance. This month we will explore bony injuries.

“It’s just a stress fracture; I can keep going.”

“I only take the boot/orthopedic shoe off to dance, other than that I wear it all the time. Is that OK?”

“I can prevent shin splints by stretching my calves more.”

As dancers, teachers, or allied health professionals, we’ve likely experienced situations like these.

What are some essential pearls that dancers, teachers, and allied health providers need to know when it comes to preventing and caring for bony injuries?

What are the most common bony injuries in dancers?

At this time, research does not clearly differentiate dancers versus other athletes with regard to bony injury; however, common bony injury sites for athletic youth and adults including dancers will be discussed here.

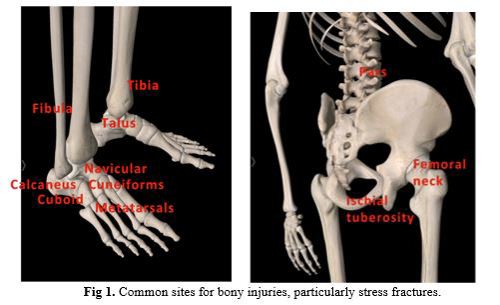

Common sites for bony injury, particularly stress fractures, include metatarsals, tibia, fibula, navicular, talus, calcaneus, and pars interarticularis.1,2,3,4 Teens and youth are also susceptible to injuries involving epiphyseal (growth) plates. See Fig 1. for an illustration of these common locations.

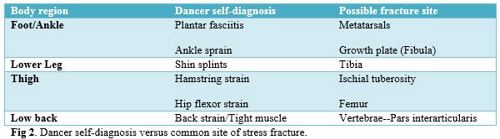

Clinically, I also find that many dancers think that they have a chronic muscle strain as opposed to a bony injury, especially when fractures are located in the back, pelvis, hip, shins, or feet (Fig 2). For example, dancers often enter the clinic with a self-diagnosis of “hamstring strain,” “hip flexor strain,” “back strain,” “plantar fasciitis,” or “ shin splints.” Once medically evaluated, many of these are found to be fractures.

Now that we’ve taken a look at common sites of bony injury, let’s get into some common myths and alternative views surrounding these bony injuries! We will delve into management tips, and foundations for designing your own injury prevention programs.

Myth # 1: It is OK to dance on a stress fracture.

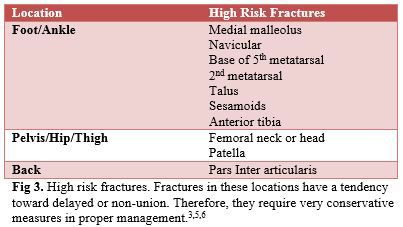

Fact: Dancing on any fracture is not recommended. A stress fracture indicates excessive loading to the involved bone, typically over a period of time; this is different than an acute fracture, which occurs in a single episode.3 Continuing to dance on any fracture can lead to a non-union where the bone terminates its healing process; this is an undesirable outcome as it can lead to needing to permanently modify activity choices. High-risk locations are much more susceptible to delayed or non-union injuries.3,5,6

Myth #2: All ankle and foot injuries should be treated with PRICE (protect, rest, ice, compress, elevate) for 2-3 days followed by gradual return to activity as long as they don’t show excessive swelling and bruising at first.

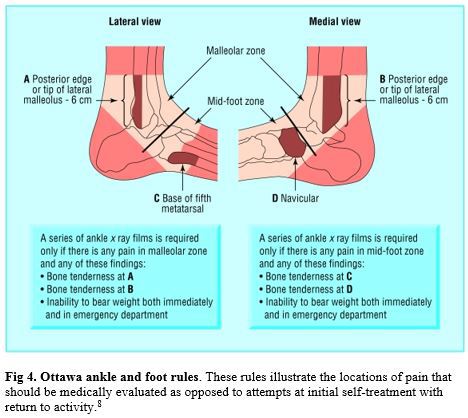

Fact: Many bony ankle injuries actually do not swell and bruise extensively immediately. Many can also take more than two weeks to show on an X-ray image.3,7 There are a few indicators that should lead a dancer to see a medical provider initially, as opposed to trying self-treatment for a few days. These indicators are known as the Ottawa ankle rules, and further medical evaluation should be performed. If there is bony tenderness to the distal 6 cm of the medial or lateral malleolus, posterior edge or tip of either malleolus, talar neck, navicular, or base of the 5th metatarsal, medical evaluation is indicated (Fig 4).8 Additionally, if there is inability to weight bear to walk at least four steps either at the time of injury or subsequent time, medical evaluation is indicated. 8

Myth #3: Once a fracture has healed, the dancer can return to his/her previous level of dance immediately.

Fact: Return to activity is guided by the high versus low risk classification of the fracture, the extent of the injury, and the typical training or competitive schedule for the individual.9 Generally, stress fractures take 6-8 weeks to heal with proper rest and rehabilitation; 7 the high risk sites can take quite a bit longer to heal.2,3 Low back fractures typically have a minimal healing time of 3 months.6

Proper management of a stress fracture goes beyond bone healing. Ligamentous laxity, leg length differences, areas of joint hyper or hypomobility, and neuromuscular imbalances can all play a role in minimizing improper loading forces through the body.3 Rehabilitation professionals also often use functional test batteries to determine the neuromuscular control of the involved body part prior to returning a dancer to activity.

Additionally, comprehensive management of a stress fracture is not limited to physical rehabilitation. Training schedules, adequate recovery strategies, fatigue management, nutrition, medications, menstrual cycle patterns, and footwear should also be evaluated.3

Myth #4: Stretching the calves regularly will prevent shin, ankle, and foot bony injury.

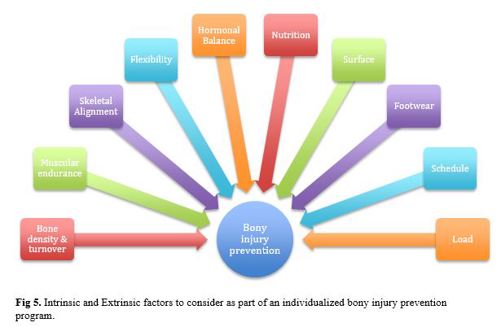

Fact: Injury prevention requires a comprehensive approach in managing multiple risk factors. Risk factors are commonly divided into intrinsic (a property of the individual human body), and extrinsic (the environment surrounding the individual). Intrinsic risk factors include bone density, skeletal alignment, flexibility, muscular endurance, bone turnover rate, hormonal balance, and nutrition.10 Extrinsic factors include dance surfaces, footwear, training schedules, and load.10 All of these factors need to be considered with regard to the individual performer (Fig 5).

Concluding thoughts:

Now that we’ve explored bony injury myths, and samples of current recommendations in prevention & treatment, how will you utilize this information in your practice?

Meredith Butulis, DPT, MSPT, OCS, CIMT, ACSM HFS, NASM CPT, CES, PES, BB Pilates is a dance-specialized Physical Therapist, Personal Trainer, Pilates Instructor, and dance performer. With over 15 years of experience, she is based in Minneapolis, MN at Twin Cities Orthopedics and the Minnesota Dance Medicine Foundation.

References

1. Brunker PD, et al. Stress fractures: a review of 180 cases. Clin J Sports Med. 1996; 6(2): 85-9.

2. Bennell KL, Brunker PD. Epidemiology and site specificity of stress fractures. Clin Sports Med. 1997. 16(2): 179-96.

3. Mayer SW, Joyner PW, Almekinders LC, Parekh SG. Stress Fractures of the Foot and Ankle in Athletes. Sports Health. 2014;6(6):481-491.

4. Smith PJ, Gerrie BJ, Varner KE, McCulloch PC, Lintner DM, Harris JD. Incidence and Prevalence of Musculoskeletal Injury in Ballet: A Systematic Review. Orthopaedic Journal of Sports Medicine. 2015;3(7)

5. Behrens SB, Deren ME, Matson A, Fadale PD, Monchik KO. Stress Fractures of the Pelvis and Legs in Athletes: A Review. Sports Health. 2013;5(2):165-174.

6. Standaert CJ, Herring SA (2007). Expert Opinion and Controversies in Sports and Musculoskeletal Medicine: The Diagnosis and Treatment of Spondylolysis in Adolescent Athletes. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 88(4): 537-40.

7. Verma RB, Sherman O. Athletic stress fractures: part I. History, epidemiology, physiology, risk factors, radiography, diagnosis, and treatment. Am J Orthop. 2001; 30(11): 798-806

8. Bachmann LM, Kolb E, Koller MT, Steurer J, ter Riet G. Accuracy of Ottawa ankle rules to exclude fractures of the ankle and mid-foot: systematic review. BMJ. 2003;326(7386):417.

9. Deihl JJ, Best TM, Kaeding CC. Classification and return-to-play considerations for stress fractures. Clin Sports Med. 2006 Jan;25(1):17-28, vii.

10. Bennell K, et al. Risk factors for stress fractures. Sports Med. 1999 Aug;28(2):91-122

Further Reading

1. Robson B, Chertoff A. Bone health and female dancers: Physical and Nutritional Guidelines Resource Paper. International Association of Dance Medicine and Science. 2010. Available at: http://c.ymcdn.com/sites/www.iadms.org/resource/resmgr/resource_papers/bone_health_female_dancers.pdf