Heels Down During Jumps…Technique or Physics?

Author: Samantha Panos on behalf of the IADMS Dance Educators' Committee

As dancers, we have all been told at one point to put our heels down when we land our jumps. As teachers, we may feel like we are constantly nagging our students to put their heels down. But why is preparing and landing from jumps with heels down important? Is it just good technique or does it play a larger role in performance capacity?

First, it may be helpful to start with a brief review of lower leg anatomy. For the purposes of this post we will focus on the posterior (back) compartment of the leg and plantar (bottom) surface of the foot as the emphasis of this entry is on the importance of heels down. Additionally, the following concepts can also be applied to the anterior (front) thigh which I will reference briefly for a more complete picture.

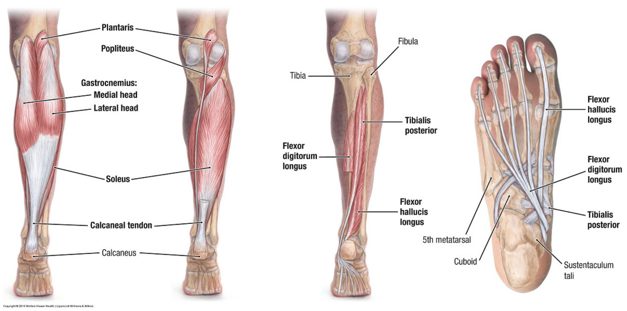

The posterior leg consists of two compartments of muscles, the superficial and deep posterior. The superficial compartment includes the gastrocnemius and soleus muscles which form the common Achilles or Calcaneal tendon, and attaches to the calcaneus (heel) bone. The resulting action of these muscles is planter flexion or “pointing” of the ankle. The soleus muscle is largely a postural muscle that is highly active in stabilizing the leg on the ankle while standing and balancing, while the gastrocnemius is a powerful muscle that plays a large role in high-velocity or forceful activities, such as jumping. The deep compartment includes the Flexor Hallucis Longus (FHL), Flexor Digitorum Longus (FDL) and the Tibialis Posterior (TP). The tendons of these muscles all pass behind the ankle, along the medial (inner) side, and enter the foot where they have various attachments as seen in Figure 1 below. These deep muscles have multiple actions but their common action is plantar flexion of the ankle.

Figure 1. Superficial Leg Compartment (Left two), Deep Posterior Compartment (middle), Plantar surface of foot (Right) showing the tendon attachments of the deep posterior compartment. (Curtesy of Duke Anatomy Lab. Web.duke.edu)

Next, let’s briefly review forces and energy. There are many types of forces that the body undergoes or can produce but for this article we will focus on tensile (tension) force. Tensile force is when a material, in this case muscles and tendons, is lengthened. The stretching or lengthening of muscles and tendons creates elastic or strain energy. Now, it is also important to understand that energy can neither be created or destroyed, it simply changes form. So, while the muscles and tendons are lengthened (tensile force) they are storing elastic potential energy and when they release and go back to their normal resting length, the energy transfers to kinetic energy. An example that is commonly used is a rubber band. Pull on the rubber band and you have elastic potential energy, let go of the band and kinetic energy is released.

Now that you feel more comfortable with posterior leg anatomy, tensile force and transfer of energy, let’s move into the studio to see how everything connects!

Whether the allegro is to a heavy 4/4 or a brisk 6/8, technique tells us that you do a demi plie to prepare for and land from a jump. The demi plie is the most critical part of the jump as a whole because it is where the musculoskeletal system generates, stores and releases energy to perform the jump. In Figure 2 below, the red arrows are showing tensile forces in the leg during a demi plie. Again, for the purposes of this post we are focusing on the plantar surface of the foot and the posterior leg as they relate to the ankle joint (the arrow along the anterior thigh is showing that in a demi plie the quadriceps muscles and the quadriceps tendon are also under a tensile load, therefore the concepts of discussion and the importance of demi plie during jumps is also applied to this region and to the knee). As you can see in Figure 2, the plantar surface of the foot and posterior compartments of the leg are being stretched – they are under tensile load in a demi plie. Therefore, elastic potential energy is being stored in these compartments and is waiting to be released as kinetic energy during the jumping phase, only to land again in a demi plie and repeat the energy storage cycle. Having the heels down throughout the preparation and landing phase of the jump allows for this efficient transfer of energy back and forth and allows the tendons and muscles to undergo a full stretch-shortening cycle. A dancer that uses their plie and keeps their heels down will generate more power and be more physiologically efficient because they are properly utilizing and transferring their energy. You would be correct to expect that as a result this dancer will jump higher and have more endurance throughout the combination.

Figure 2. Force vectors indicating tensile forces in muscle groups during a demi plie. (Panos, Samantha. (2006). The Physics of Ballet. (Unpublished Masters Thesis). University of Utah, Salt Lake City, Utah)

But now what happens when jumps are landed with heels off the ground? In this scenario the dancer will deplete themselves of all the benefits previously discussed. The muscles and tendons will still undergo a tensile load but of less magnitude, therefore less elastic potential energy will be stored and less will be released. Going back to the rubber band analogy, pull hard on the rubber band and it will shoot across the room when you release it, pull lightly (less stretch) and it will travel a shorter distance. Can you see how this is not optimal for your students or as a dancer yourself? Less potential energy means you will have to fight through the jumps and you will not recover in between each jump, in turn, fatiguing faster.

Lastly, jumping with heels down will also help prevent injury by allowing for these compartments to go through their full stretch-shortening cycle. Landing with the heels up means the Achilles tendon and the smaller tendons of the deep posterior compartment do not get to fully lengthen during the impact of the landing. Repeated landing with heels up, such as during a petite allegro, means all the tendons of the posterior leg stay shortened to a degree and therefore are not able to absorb the force of impact, store adequate energy or release energy efficiently, so they are being taxed at a higher rate. Over time, this technique error will likely result in posterior leg/ankle overuse pathologies such as tendinitis including the most common Achilles tendinitis or the commonly under diagnosed FHL tendinitis as well as other inflammatory diagnoses. Dancers will complain of posterior ankle pain and most likely assume it is Achilles tendinitis which may or may not be the case, but addressing the proper use of their demi plie during jumps may help to calm or prevent the injury all together.

Now, you may be thinking, does this information apply to other dance movements as well? Yes, it would. Consider repeated releve’s, pirouettes from fifth, fouette turns, etc. Any time the dancer is required to go from foot flat on the ground to demi pointe, full pointe or jumping, all of the information about the posterior compartments stretch-shortening cycle, tensile force, storage and transfer of energy is relevant in performance efficiency and prevention of injuries.

Samantha Panos PT, DPT, MFA is a dance educator, former dance teacher and Physical Therapist at Dynamic Physical Therapy in Salt Lake City, Utah whose goal is to educate and inspire young dancers, encourage cross training for overall dancer health and to reduce injury by promoting proper technique to achieve maximal physiologic efficiency and performance capacity.

Recommended Readings

- Alexander RM. Tendon elasticity and muscle function. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part A. 2002; 133:1001-1011.

- Kim S. An Effect of the Elastic Energy Stored in the Muscle-Tendon Complex at Two Different Coupling-Time Conditions During Vertical Jump. Advances in Physical Education. 2013;3(1):10-14.

- Silbernagel KG. Nonsurgical Treatment of Achilles Tendinopathy. In: Doral M., Karlsson J. (eds) Sports Injuries. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg. 2014.

*Note: the recommended reading Nonsurgical Treatment of Achilles Tendinopathy is not to take the place of professional medical advice. If you or your dancer are experiencing posterior ankle pain, please seek medical attention from a physician or a Doctor of Physical Therapy to guide you through the appropriate treatment options for recovery. This reading is only intended to provide insight into the prevalence and potential causes of Achilles tendinopathy and to provide realistic expectations into recovery time frame.